2: CITIES, LIVES AND MEMORIES

Timeless cities of then, of now and of undying memories

In this section, I share my impressions and anecdotes from the cities I’ve lived in, from past to present, along with excerpts from my travel journals and the New Year’s letters I’ve been writing since December 2005.

25 chapters (see Table 1) spent in 18 cities— some of them being a return to the same one place several times —and some of which were more prominent, and a part of me still feels “from there.” Others left less visible marks —vague memories, or traces of things I’ve been told, even if I don’t remember them. If someone asks which city is your “real city,” it’s very difficult to answer. This degree of “prominence” and “importance” is experienced more as a gut feeling. However, I once tried to establish a more “scientific” basis for this by determining some criteria for what might connect you most to a city (how many years have you lived there, how many years have passed since you left, and any active friendships you have from there) and assigning them points. Then there is the beauty, attractiveness and quality of life in cities, of course. But for some reason, at the end of the day, this isn’t the most important criterion. We can admire cities for their beauty, but I think our attachment to them is based on other things…

Yes, the question “where are you from?” is a very difficult one for some to answer. My census registry (“kütük”) is still my father’s, the Nazilli district of Aydın, but since I don’t go there except for a few days’ vacation visits every two or three years, I couldn’t even include it in the table below. While I feel some connection to our relatives, homes, and fields there, it’s an abstract one. There’s also the fact that my mother’s family is settled in Izmir, and we used to go there during semester breaks as a child. However, I only gave Izmir a single line in the table. When some people ask, Nazilli is the shortcut. But the real answer is a complex story that demands a long paragraph. Some people have only one city, and you go between feeling sorry them and envying them. This search for a homeland ultimately finds a solution by embracing it all, by becoming a “citizen of the world.”

Yes, the question of “where are you from?” is a very difficult one for some to answer. My hometown is still my father’s, the Nazilli district of Aydın, but since I don’t go there except for a few days every two or three years for vacation, I couldn’t even put it in the table below. While I feel connected to our relatives, our homes, and our fields there, it’s an abstract attachment. My mother’s family also lives in Izmir, and we used to go there during semester breaks as children. However, I only gave Izmir a single line in the table. When some people ask, Nazilli is the shortcut answer. But the real answer is a complex story that requires a long paragraph. Some people have only one city, and you feel a wavering feeling of pity and envy for them. This search for a homeland ultimately finds a solution by embracing it all, by becoming a “citizen of the world.”

Table 1: Chronology of cities lived in

| 1. Geneva | (1975-76) | 6 months | |||||

| 2. Kuşadası | 1976-97 | 22×2 summer months | |||||

| 3. Bangkok | 1976-78 | 2 years | |||||

| 4. Ankara | 1978-80 | 1983-85 | 1989-93 | 1994-98 | 2000-06 | (2007-08) | 2+2+4+4+6+0.5=18.5 years |

| 5. Tabriz | 1980-81 | 1 year | |||||

| 6. Izmir | 1981-82 | 1 year | |||||

| 7. Rome | 1982-83 | 1 year | |||||

| 8. Helsinki | 1985-89 | 4 years | |||||

| 9. Teheran | (1990-92) | 1+1= 2 months | |||||

| 10. Berlin | 1993-94 | 1 year | |||||

| 11. Çeşme | 1998- | 28×2 summer weeks | |||||

| 12. York | 1998-99 | 1 year | |||||

| 13. Ulan Bator | (1999-2000) | 2 months | |||||

| 14. New York City | 2006-07 | 1 year | |||||

| 15. A.Dhabi | 2008-2012 | 5 years | |||||

| 16. Istanbul | 2013-18 | 2019-22 | 2025- | 6+3+0.5=9.5 years | |||

| 17. Gaziantep | (2019) | 6 months | |||||

| 18. Mudurnu | 2022-25 | 3 years |

Cities one lives in, visits, works for and makes a “project” out of

The cities in this table include places where I stayed for six months or more, or where our families spent the summers, and where I stayed regularly for at least a few weeks for many years. Summer resort towns became places where a nuclear family like ours, which moved frequently, could meet and spend time with their extended family, these annual summer rituals providing stability and security. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were more often seen at summer resort towns. Although these meetings are less frequent now, and while everyone lives their own lives separately, family ties with ancient roots are still a source of well-being.

Then there are cities that were regularly visited for professional reasons, for architectural, urban planning, and conservation projects, researched and analyzed, articles written about, and into which their development was given much thought and effort. One can feel a very different, special, and even strange attachment to these. The most important of these for me are Nevşehir-Ürgüp (Kayakapı) (2000-06), Abu Dhabi-Al Ain (2008-12), Aydın-Kuşadası (2008-11), Gaziantep (2008-11, 2019), and Bolu-Mudurnu (2008-11, 2013-25). I also have fond and exciting memories of Antalya-Alanya, Antalya-Demre (St. Nicholas Church), Antalya-Finike (Gökbük), Muğla-Fethiye (Kayaköy), and Istanbul-Beyoğlu (Pera Palas), where I worked on while I was employed at an architecture firm between 2000-06. After 2015, my consulting work, while based in Istanbul, took me to locations like Eyüp, Istanbul (2015-16), Ereğli, Konya (Ivriz) (2015-16), Boğsak, Mersin (2015-17), and Izmir (Kemeraltı – Historic Port City) (2021-22). As you get to know the places you work in, you may become a deeply concerned stakeholder in them, and throughout your life you wonder how they’re developing and wish good things to happen there. You develop a connection to each city’s personality, as if they were each a human being.

Positioning oneself against the city

Each person has an individual, unique relationship with a city, based on their own state of mind, consciousness and experiences…

The city gets redefined and reinvented every time you look at it…

And maybe, every city in turn reinvents the person, again and again, adding yet another layer of memory, consciousness and identity…

We are haunted by our ‘previous lives’ in these cities, too. All the remaining ‘patina’* from these lives can at times give us a mysterious shadow..

Thus, I have many kinds of such layers. I am like the mound of an ancient city (a ‘tell’, or a ‘höyük’), or maybe like a ‘baklava’ pastry; if they did my archaeological excavation it would make a whole museum, complete with its resident ghosts! Hahaha!..

(* A special layer of dirt and soot that builds up over old buildings, which can enhance the value of historic buildings and protect their surfaces and which needs care during cleaning.)

Settling in to the city

With every arrival in a new place, there are first impressions that pass trough one’s mind related to the people and atmosphere of that place. Then, as one thinks a little more about it and accumulates enough similar impressions, one starts to make more self-confident analyses and generalizations, even forming slight stereotypes.. Some easy and ready answers are formulated to questions like “why is this place the way it is”, “why are people here the way they are”, “what makes it so”, etc.

New house, new neighborhood, new city, new country, new job (or even new line of work), new daily rhythm. New institutions, colleagues, acquaintances, friends. These are added on to old ones remaining from other places, and contribute to the accumulation of layers.

How do you get used to a city, how do you make it yours? One aspect of this is logistics: navigating yourself, getting errands done, etc. Another aspect is emotional comfort: making friends and having a social life, develoing routines in the city that make you feel good. These are on a personal level. And then there is the public dimension. The shared spaces, elements, symbols of the city… If you have a concern or passion about their protection and staying in use and accessible, if you care what happens to them, in other words, if you become a ‘stakeholder’ there, then your sense of belonging deepens. When you visit that city again and see its familiar elements, even years later, something stirs inside you. In that case, that city has a ‘genius loci’ (Latin for ‘sense of place’) for you.

Flying from city to city

For us mobile types, inter-city traveling is a constantly repeated activity that becomes second nature, with its luggage customized according to the length of stay and the climate of the destination, and its documents (passports, visas, electrical socket adaptör, etc.) customized according to whether one is also crossing country borders.

Something I love to do, especially when I am not steering the vehicle myself, is to watch the changing landscape from the window. This is also a ‘window of time’ where you can daydream, make connections between the things you see going by and other things about life that come to your mind, but which feels like ‘enforced holiday’, since you have a restricted, often predetermined amount of free time to do it. Buses, trains, ferries, boats (cars are my least preferred mode to do this) are all suitable for this ‘gazing’ activity, but airplanes have a special place. The landscape you watch is aerial (or surreal?), and if you are a map-lover like me, seeing ‘real maps’ down below in the awe-inspiring geography of the Earth is a great treat.

We have taken off into the atmosphere, cruising, up above the clouds… Excerpt from diary entry written on board: “Sunshine hits the white clouds, the silver wing sears them… I love flying (as long as there is no turbulence!). It is a blessing and a privilege; I am thankful that I can do it often… Mobility is one of the most precious assets in my life. The freedom to move. One of the great freedoms, that not all of us have, like the freedom to: think, speak, organize, write, work, drive, vote, lead, love and marry.. The clouds I see from the window make a gorgeous changing landscape one after the other. This is the greatest thing about flying, for me..!”.

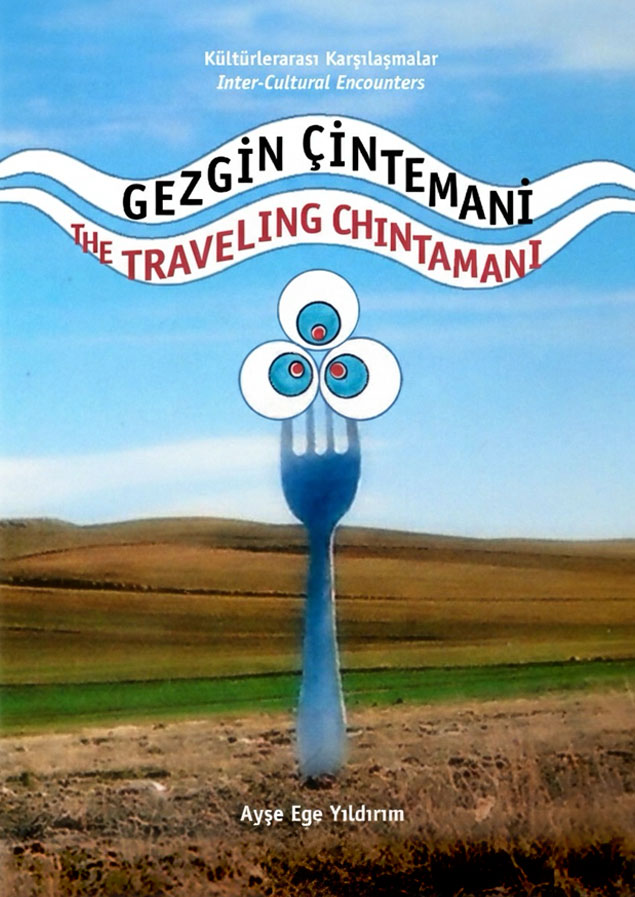

1: INTRODUCTION: THE TRAVELER AND THE CHINTAMANI

In 2014, shortly after moving from Abu Dhabi to Istanbul, I started a book writing project.

It’s a mix of autobiography and essay genres. I was working on it simultaneously in Turkish and English, having written about 100 pages in each language. But over the past decade or so, both my environment and I changed, and the text got somehow outdated.

I have now started revisiting this project. I decided to update and complete some sections I felt worth sharing. So here I am. Regads from the Traveling Chintamani…

“The Traveler”

They say, “one cannot be explain it, one must experience it,” but one must also write it … Writing, as you know, could be considered a kind of self-therapy, or a way to make sense of situations not possible to make sense of otherwise.

For many years—in other words, for most of my life— I wrote and took notes for myself as I was swept from city to city, country to country, culture to culture and mood to mood.

Sharing is the twin sister of writing. What we really want to do through writing is to confide in someone. That someone is first ourselves, sometimes just ourselves. Then, sometimes, others. Throwing ideas into the world, into space, saying, “Let’s do it, for what it’s worth!”

So that others might enjoy reading, identify with and benefit from what we write. To leave a unique, albeit small, note for the historical record. Or we share out of a desire for others to appreciate and understand us. In today’s digital technology and social media environment, there’s no need to even discuss these things… Despite all the pollution and overdose of information, our ability to share meaningful things remains eternal; we are, after all, human.

I am a big traveler. This stems primarily from my being a diplomat kid. These diplomatic childhood travels later became ones made in adulthood for: graduate studies, living abroad as an ‘expat’ for work, and after relocation home permanently, regular business and social travel. What emerged was an “international Turk.”

In my book endeavor, the Traveling Chintamani, I attempt to talk about the life of one of these diplomat kids (or “third culture kids”), telling the strange and funny stories that come along with it.

I first thought about examining the state of us diplomat kids (or ‘diplobrat’s as some may prefer, if they want to allude to our possibly being spoilt..) as a project during my college years (c.1996). While wondering if there were any Turkish studies on this topic, I learned that the Americans had (of course, if anyone had, they would have been the first to do it!). First, I found a study by the US State Department (on state.gov; the link is obsolete), then the work of an anthropologist (Ruth Hill Useem), and then the web portals created by the 3CKs themselves. (The most concise definition of 3CK is, in Useem’s words: “children who accompany their parents into another society.”) On whether or not the information in these sources would apply to all the ‘international kids’ of the world, I would say not 100 percent, as it would need to be adapted to the local cultural contexts; however, there are bound to be many common characteristics.

If I were to summarize the meaning of this life for me personally, I should first say that, the nuclear family made up of my mother-father-sister and me has been fundamental, in terms of the support and solidarity we received from each other during our childhood and youth, whenever we felt like aliens in all those different, disconnected places. As for the few weeks spent with extended family during the summer holidays, these made it possible for us to maintain ties, however imperfect, with our “homeland”.

Constant or regular traveling and relocation and living in many different places brings an incredible need for mobility on one hand, and fosters the habit and skills of ‘settling in’ and ‘becoming local’ in the places of residence in a short span of time, on the other. You become a chameleon, so to speak. Adapting = surviving… Furthermore, when you realize that every moment that makes up your life is significant and valuable in itself, you have to find a way to enjoy the place you are, rather than wait for the difficult stays to be over.

Flying from branch to branch, resting for a short while on one, flying away again, taking off into far horizons… At times it is a relieving sense of freedom, at other times a feeling of loneliness and disconnectedness that weighs life down. Being a kind of ‘eternal tourist’ and observer.

I suppose this would make us quite fit for a career in the fields of diplomacy, culture and tourism. Our relationship with ‘place’ and ‘the earth’ are constant themes or sub-texts in the fields of architecture, planning, geography and cultural heritage. By looking at places and cultures at a macro level and from an analytical perspective, one may have a chance to alleviate the feeling of being stuck between places and cultures and to channel it into useful activities, to a certain extent at least.

Speaking of looking of things at a macro level, making connections between different events and subjects would also seem an enjoyable and natural pursuit for us mobile types. Perhaps this is why I like being a ‘generalist’. In this book, I explore my own professional field of urban planning and cultural heritage preservation, with interpretations based on personal observation, common sense, and intuition.

“The Chintamani”

So, I think you understand the “traveler” part of the book’s title. As for the ‘Chintamani’ part, I am guessing that many of us would have had a chance to see this symbol, which has long fascinated me, in museums, exhibitions, and souvenir shops dedicated to Ottoman art. As for me, I have grown even fonder of it after I copied its pattern printed on a pillow in my parents’ home and took it to be tattooed on my arm in 2001. Imprinting an artistic motif characteristic of Turkish culture into my own body and carrying it around with me thereafter, seems to have found its meaning as a symbol of the identities etched in our being…

I know a little something about the meaning, and the historical, and cultural significance of the Chintamani pattern from what I’ve read over the years, but now I’ve browsed a few articles again (like Bulut 2018, iznikmavicini.com, Paralı and Mangır 2024, Wikipedia/cintamani), and then asked ChatGPT, to give me a summary. (We’ve entered the age of Artificial Intelligence, so why not? Let’s take advantage of it, right?)

“The Chintamani pattern is an ancient motif originating in Central Asia, widespread in Turkish-Islamic art, particularly during the Ottoman period. Its name comes from the Sanskrit word “cintamani” (wishing stone, lucky jewel), and carries meanings such as power, strength, happiness, and protection. The pattern generally consists of three rounded shapes (triple pearls or spots) and two wavy lines (tiger hide or cloud motifs) next to or between them. It was used in Ottoman palace caftans, tiles, book decorations, and textiles from the 15th century onward.” It became a symbol of sovereignty, symbolizing the sultan’s power, wisdom, and justice. Because it reflects both cosmic powers and worldly authority, the Chintamani motif is also considered a “symbol of Ottoman power. “”

It feels very good for me to embrace as an identity, the story of Chintamani’s arrival from the East and its Westernization in Anatolia within Turkish art. I, too, am a “Western Easterner”; a Turk and a citizen of the world. I strive to be a nationalist, patriot, committed to my homeland, and socially conscious, while having a free, inclusive nature, belonging both everywhere and nowhere. Let’s define it this way. We are what we define ourselves to be, aren’t we?